Every year, thousands of people start chemotherapy or biologic therapy for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, or other autoimmune diseases. They’re focused on fighting their main illness - but many don’t realize they’re walking into a silent, potentially deadly trap: HBV reactivation.

HBV reactivation isn’t a new infection. It’s the virus waking up inside you. If you’ve ever had hepatitis B - even if you thought you beat it - your immune system kept it asleep. Then comes chemotherapy, rituximab, or another powerful drug that shuts down your immune defenses. Suddenly, the virus starts copying itself like crazy. Liver enzymes spike. Jaundice appears. In severe cases, the liver fails. And it can happen fast.

This isn’t rare. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable.

Who’s at Risk? It’s Not What You Think

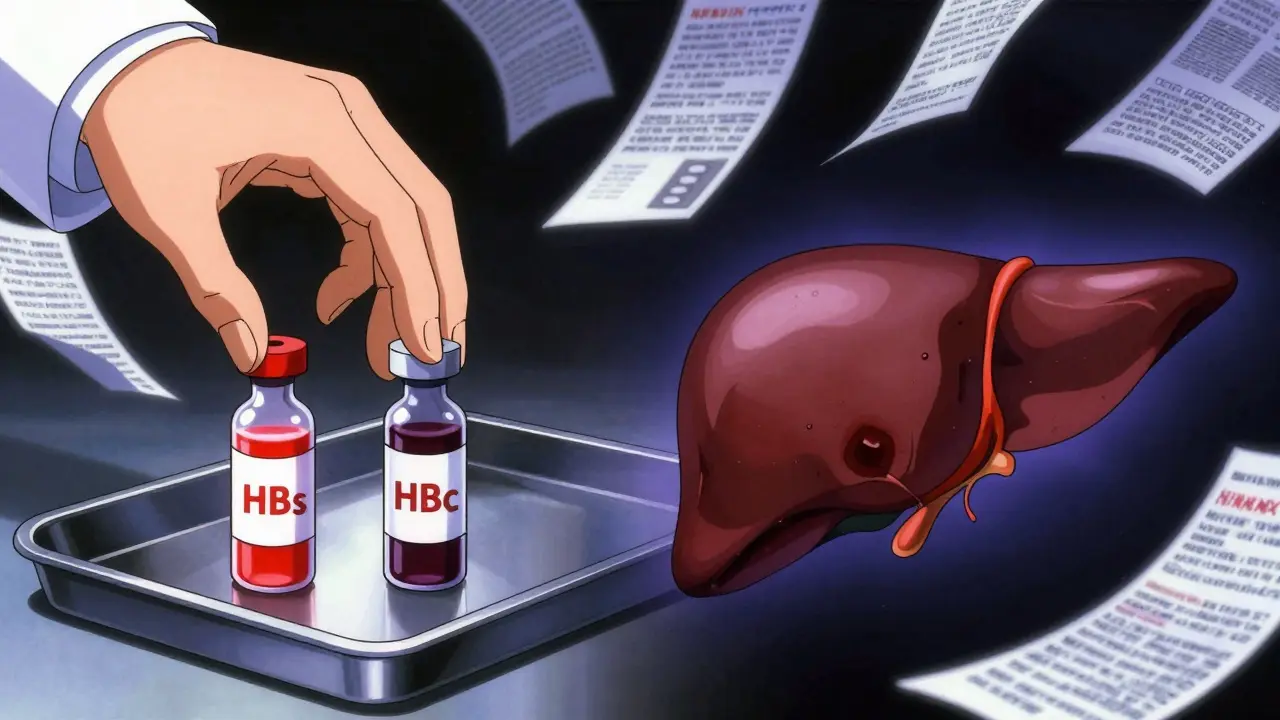

Most people assume only those with active hepatitis B (HBsAg-positive) are at risk. That’s only half the story.

If you’re HBsAg-positive - meaning the virus is still in your blood - your risk of reactivation is terrifyingly high. With drugs like rituximab (used for lymphoma), up to 73% of patients will see the virus come roaring back. Even standard chemo without steroids can trigger reactivation in 20-50% of carriers.

But here’s what catches doctors off guard: people who think they’re clear. Those with resolved hepatitis B - HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive - still carry the virus in their liver cells. Their immune system kept it quiet. Then comes immunosuppression. In high-risk settings like stem cell transplants or aggressive chemo, 10-18% of these patients will suffer reactivation. One study found 18% of resolved HBV patients on high-dose chemo developed liver failure. Half of them died.

Even radiation therapy isn’t safe. A 2020 study showed a 14% reactivation rate in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive liver cancer patients after radiation. And checkpoint inhibitors - the new cancer immunotherapies - have a 21% reactivation rate in HBsAg-positive patients who weren’t on antivirals.

It’s not just cancer. Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease - especially TNF-alpha blockers and B-cell depleters like rituximab - carry a 3-8% risk in resolved cases. That’s not low. That’s a ticking clock.

The Three Stages of HBV Reactivation

It doesn’t happen overnight. There’s a pattern.

Stage 1: Viral Replication

Within weeks of starting immunosuppression, the virus starts multiplying. HBV DNA levels rise in the blood. But the patient feels fine. Liver enzymes? Normal. No symptoms. This is the silent phase. Most patients and even some doctors miss it because there’s no warning.

Stage 2: Immune Reconstitution Hepatitis

This is the crash. As the immune system starts to recover - either naturally or after stopping treatment - it attacks the infected liver cells. The body turns on itself. ALT and AST levels skyrocket. Fever, nausea, dark urine, yellow eyes. In 10-20% of cases, this leads to acute liver failure. Death can follow in days if not treated.

Stage 3: Resolution

If the patient survives, the virus gets suppressed again. But liver damage may be permanent. Cirrhosis, liver cancer, or the need for a transplant can follow.

This isn’t theoretical. A 52-year-old man with lymphoma got rituximab without screening. He died of liver failure two months later. His medical records showed he’d been HBsAg-positive as a teenager - a fact his family didn’t know, and his doctor never checked.

How to Prevent It: Screening and Prophylaxis

There’s one rule: Screen everyone before starting immunosuppression.

Two simple blood tests:

- HBsAg - tells you if the virus is currently active

- anti-HBc - tells you if you’ve ever been infected

If HBsAg is positive - you’re a carrier. Start antivirals before chemotherapy or biologics. Tenofovir or entecavir are the gold standards. They block viral replication. Start at least one week before treatment begins.

If HBsAg is negative but anti-HBc is positive - you’re a resolved carrier. You still need prophylaxis if you’re getting high-risk therapy: rituximab, stem cell transplant, anthracycline chemo, or high-dose steroids. For moderate-risk therapy (like TNF blockers), monitor HBV DNA monthly. If it rises, start antivirals immediately.

For low-risk therapies - like non-TNF biologics or most targeted drugs - monitoring alone is usually enough. No need to start antivirals unless the virus reappears.

Prophylaxis isn’t just a precaution. It’s life-saving. In one study of 1,245 HBsAg-positive patients, those on antivirals had a 3.2% reactivation rate. Those without? 48.7%. That’s a 93% drop in risk.

How Long Should You Stay on Antivirals?

For years, doctors told patients to stay on antivirals for 12 months after finishing immunosuppression. That’s changing.

A landmark 2022 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 6 months of antiviral treatment after therapy ends is enough for most patients. Only those with very high-risk regimens - like stem cell transplants or rituximab - need 12 months.

Stopping too early? Risk of rebound. Staying on too long? Unnecessary cost, side effects, and drug resistance. The goal is precision, not blanket coverage.

For patients with resolved HBV on moderate-risk therapy, stop antivirals only after 6-12 months of normal liver enzymes and undetectable HBV DNA. Monitor for at least 12 more months after stopping.

Why So Many Patients Still Get Hit

Screening works. But it’s not happening.

A 2020 survey found only 58% of community oncologists follow screening guidelines. In academic hospitals? 89%. Why the gap?

- Doctors don’t know the guidelines

- Patients don’t know their HBV status

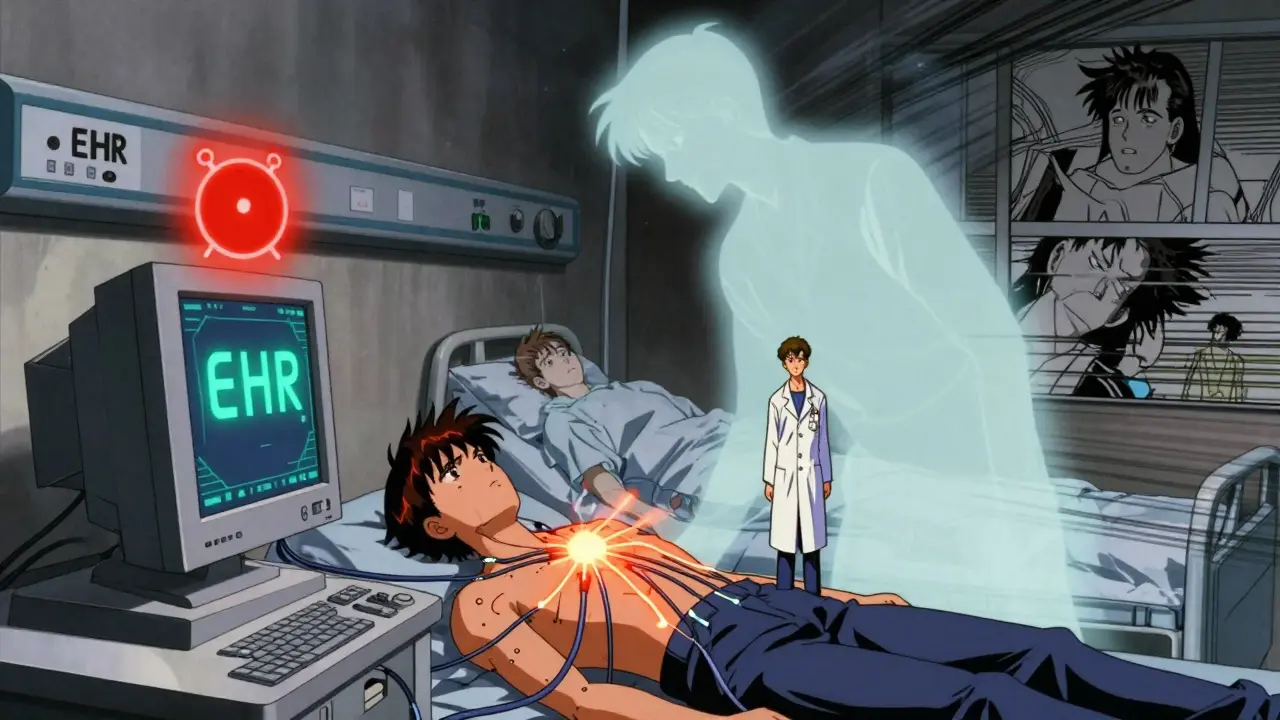

- Screening isn’t built into electronic health records

- There’s no one to follow up

At UCSF, they fixed it with an automated alert in their EHR. If a patient is scheduled for chemo and hasn’t been screened, the system blocks the order until testing is done. Result? Reactivation rates dropped from 12.3% to 1.7% in five years.

At Memorial Sloan Kettering, they use automated flags to track patients through treatment and beyond. If a patient stops antivirals too soon, the system sends a warning to the oncologist.

These aren’t fancy tech tricks. They’re basic safety checks. And they’re not optional.

The Cost of Doing Nothing

The cost of screening? $20-$50 per patient.

The cost of treating HBV reactivation? $50,000-$200,000. Hospitalization. ICU. Liver transplant. Lost income. Death.

And it’s not just money. A 2019 study found that 12% of infectious complication lawsuits in oncology involved HBV reactivation. Families sue. Doctors lose licenses. Hospitals pay millions.

Dr. Robert Gish of the Hepatitis B Foundation says it plainly: “The cost of screening is negligible compared to the human and financial costs of managing reactivation.”

Yet in the UK, US, and Europe, many clinics still don’t screen. Why? Out of sight, out of mind. Patients don’t know. Doctors don’t ask. And the virus waits.

What You Need to Do - Right Now

If you’re about to start chemotherapy, rituximab, or any biologic:

- Ask your doctor: “Have I been screened for hepatitis B?”

- If not, demand HBsAg and anti-HBc blood tests - before your first treatment.

- If you’re HBsAg-positive, confirm you’re starting antivirals at least one week before treatment.

- If you’re anti-HBc-positive, ask if your therapy is high-risk and whether you need prophylaxis.

- Don’t stop antivirals unless your doctor says so - and even then, get follow-up blood tests.

If you’re a healthcare provider:

- Build screening into your protocol. Every patient. Every time.

- Use EHR alerts. Make it automatic.

- Know your risk levels. Rituximab = high. TNF blocker = medium. Steroid cream = low.

- When in doubt, treat. Better safe than sorry.

This isn’t about complex medicine. It’s about basic care. A $30 blood test. A $10-a-day pill. A 6-month commitment. That’s all it takes to prevent death.

HBV reactivation is one of the most preventable tragedies in modern medicine. We have the tools. We have the guidelines. We just need to use them.