When you’re on antiplatelet meds like aspirin or clopidogrel, you’re not just preventing a heart attack or stroke-you’re also putting your stomach at risk. These drugs stop your blood platelets from clumping together, which is great for your heart but not so great for your gut. About 1 in 100 people on these medications will have a serious bleed in their stomach or intestines within the first month. And for those on dual therapy-say, aspirin plus clopidogrel-that risk jumps by 30 to 50%. If you’ve had a stent put in or survived a heart attack, you likely need these drugs. But you also need to protect your digestive tract. It’s not optional. It’s essential.

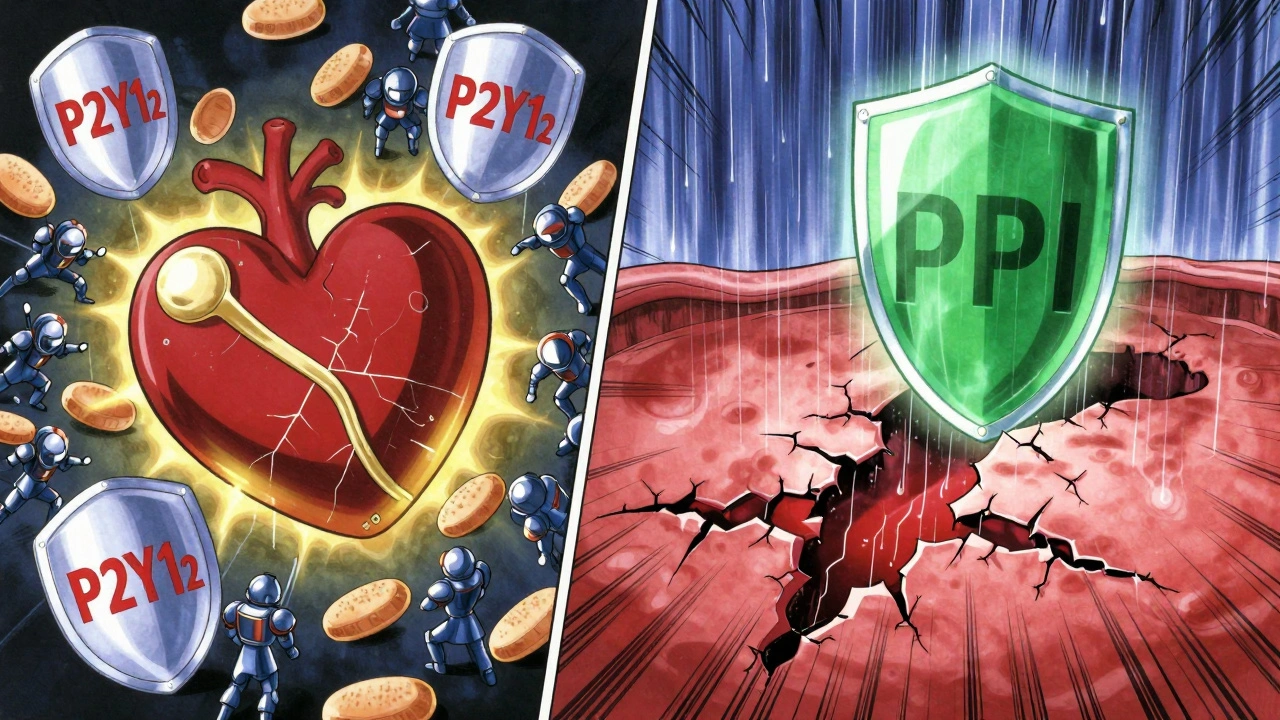

How Antiplatelet Drugs Work-and Why They Hurt Your Stomach

Antiplatelet drugs don’t thin your blood like warfarin. Instead, they shut down platelets, the tiny blood cells that start clots. Aspirin does this by blocking an enzyme called COX-1, which your stomach lining uses to make protective mucus. Without it, acid eats away at the lining. Even enteric-coated aspirin doesn’t fix this. The coating only delays when the pill dissolves-it doesn’t stop the drug from affecting your platelets systemically. That means your stomach still loses its natural defense.

P2Y12 inhibitors like clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor work differently. They block a receptor on platelets called P2Y12, stopping them from sticking together. But here’s the catch: these drugs also interfere with healing. Platelets don’t just form clots-they release growth factors that help ulcers repair. Clopidogrel suppresses that signal. Studies show it’s more likely than aspirin to cause ongoing damage, with a hazard ratio of 1.8 for developing high-risk stomach lesions. Prasugrel and ticagrelor are even stronger at preventing clots, but they also carry higher bleeding risks. Ticagrelor, for example, increases GI bleeding by 30% compared to clopidogrel, according to the PLATO trial.

Who’s Most at Risk for Gastrointestinal Bleeding?

Not everyone on antiplatelets bleeds. But some people are walking into danger without knowing it. The biggest red flags: age over 65, a history of ulcers or GI bleeding, taking NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen, having H. pylori infection, or being on blood thinners like warfarin. Combine any two of these, and your risk skyrockets.

A 2023 study of over 2,100 patients found that 40% of aspirin users and 50% of those on clopidogrel or dual therapy developed visible stomach damage within 6 to 12 months-even if they had no symptoms at the start. That’s not rare. That’s predictable. And it’s preventable.

Doctors use a simple tool called AIMS65 to spot high-risk patients: Albumin below 3.0, INR over 1.5, mental confusion, systolic blood pressure under 90, and age 65 or older. If you score 2 or higher, you’re in the danger zone. That’s not a guess. That’s science.

The Truth About Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs like esomeprazole, omeprazole, and pantoprazole are the gold standard for protecting your stomach. They cut acid production by up to 90%, giving your lining time to heal. But here’s where confusion sets in.

Some cardiologists worry that PPIs reduce clopidogrel’s effectiveness. That fear started in 2009 when early studies suggested PPIs might block the enzyme (CYP2C19) that converts clopidogrel into its active form. The FDA looked into it. Dr. Norman Stockbridge from the FDA said back in 2010, “The clinical relevance remains uncertain.” And since then, large studies have shown mixed results. A 2023 meta-analysis found no significant increase in heart attacks or stent clots when PPIs were used with clopidogrel in real-world patients.

What’s clear? If you’ve had a GI bleed, you need a PPI. Period. A 2019 survey of 1,247 gastroenterologists found 89% routinely prescribe PPIs to patients with prior ulcers on antiplatelets. And the results? One case series showed 92% of ulcers healed in just 8 weeks with esomeprazole 40mg daily. That’s not luck. That’s treatment working.

For high-risk patients, guidelines recommend starting with high-dose IV PPIs during active bleeding, then switching to oral 40mg daily. Most experts agree: keep it going for at least 8 weeks after healing. If you’ve had a complicated ulcer-bleeding, perforation, or needing surgery-stay on it long-term.

What to Do If You Bleed

If you start vomiting blood, passing black tarry stools, or feel dizzy and weak, get help immediately. But here’s what you shouldn’t do: stop your antiplatelet meds without talking to your doctor.

A 2017 Lancet trial showed that stopping aspirin during a GI bleed didn’t improve outcomes. In fact, it raised the risk of death by 25%. Why? Because the heart attack or stroke you’re trying to prevent is often deadlier than the bleed. The American College of Gastroenterology and Canadian Association of Gastroenterology now say: keep aspirin going. Always.

For clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor, pause them during active bleeding. Restart as soon as it’s safe-usually within 24 to 72 hours after endoscopic treatment. Delaying too long increases your chance of a stent clot. One Reddit thread from May 2023 had three cases where patients quit clopidogrel because of stomach pain-and all three had stent thrombosis within a month. One died.

And don’t get platelet transfusions unless you’re actively crashing. A small study found transfused patients had 27% mortality versus 12% in those who weren’t. Why? Transfused platelets don’t help if the drugs are still blocking them. You’re just adding more fuel to the fire.

What If You Can’t Tolerate PPIs?

One in five long-term PPI users develops side effects: bloating, diarrhea, nutrient deficiencies, or even kidney issues. If you can’t take a PPI, you need alternatives.

H2 blockers like famotidine are weaker but safer for some. They’re not as good at healing ulcers, but they can help with acid reflux. For patients who can’t take PPIs, doctors sometimes combine H2 blockers with misoprostol-a drug that replaces the protective mucus your stomach loses from aspirin. But misoprostol causes cramping and isn’t safe in pregnancy.

Another option: switch your antiplatelet. If you’re on clopidogrel and keep having stomach issues, ask about switching to aspirin alone. For many, it’s enough. If you need stronger protection, ticagrelor might be worse for your gut-but prasugrel is even riskier. Your doctor can weigh the trade-offs.

What’s Next for Antiplatelet Therapy?

The future is personalization. Right now, we treat everyone the same. But your genes matter. About 30% of people have a CYP2C19 gene variant that makes clopidogrel less effective. These patients are stuck between a rock and a hard place: their blood clots too easily, but they’re also more likely to bleed from the drugs they’re given.

Genetic testing is becoming more common. If you’re a poor metabolizer, switching to ticagrelor or prasugrel might be smarter-not because they’re safer for your stomach, but because they work better for you. And that means you might need lower doses or shorter courses.

Researchers are also testing new drugs like selatogrel, which blocks platelets in a different way. Early data shows 35% less stomach damage than ticagrelor. It’s still in trials, but it’s a sign we’re moving toward drugs that protect the heart without wrecking the gut.

And soon, we might use blood tests-like measuring pepsinogen and gastrin-17-to predict who’s most likely to bleed. That way, we don’t give PPIs to everyone. Just to those who need them.

Bottom Line: Balance Is Everything

You’re not choosing between your heart and your stomach. You’re choosing how to protect both. Antiplatelet therapy saves lives. But it’s not harmless. The key is matching your treatment to your risk.

If you’re on aspirin alone and have no history of ulcers? You’re probably fine. Just avoid NSAIDs and check in with your doctor yearly.

If you’ve had a stent, a heart attack, or a GI bleed? You need a PPI. Don’t delay. Don’t skip. Don’t assume it’s just heartburn.

If you’re confused about which drug to take or whether to stop one? Talk to both your cardiologist and your gastroenterologist. They need to talk to each other. You shouldn’t be the one juggling the decisions.

There’s no perfect drug. But there’s a smart plan. And with the right strategy, you can live a long life-without a bleeding ulcer stealing it from you.

Can I stop my antiplatelet medication if I have stomach bleeding?

No, you should not stop aspirin. Stopping it during a GI bleed increases your risk of death by 25%, according to a major 2017 Lancet study. Aspirin protects your heart more than it harms your stomach. For other antiplatelets like clopidogrel or ticagrelor, doctors may pause them temporarily during active bleeding, but they’ll restart them as soon as it’s safe-usually within 1 to 3 days after endoscopic treatment. Never stop these drugs on your own.

Do PPIs reduce the effectiveness of clopidogrel?

Early studies suggested PPIs might interfere with clopidogrel’s activation, but large real-world analyses since 2015 show no significant increase in heart attacks or stent clots when PPIs are used together. The FDA says the clinical relevance is uncertain. For patients with a history of bleeding, the benefit of preventing another GI bleed far outweighs any unproven risk to heart protection. If you’re on clopidogrel and need a PPI, take it.

Is enteric-coated aspirin safer for the stomach?

No. Enteric coating only delays when aspirin dissolves in the stomach-it doesn’t stop it from affecting platelets or reducing protective mucus production. The systemic antiplatelet effect remains the same. Studies show no meaningful difference in bleeding risk between regular and enteric-coated aspirin. Don’t rely on coating for protection. Use a PPI instead.

How long should I take a PPI with antiplatelet therapy?

For patients with a history of ulcer or GI bleeding, guidelines recommend at least 8 weeks of PPI therapy after healing. If you’ve had a complicated ulcer-like one that bled or perforated-long-term or indefinite PPI use is advised. For those without prior bleeding but with multiple risk factors (age 65+, on NSAIDs, H. pylori), 3 to 6 months is often enough. Always follow your doctor’s advice based on your individual risk.

Can I take ibuprofen or naproxen with antiplatelet drugs?

Avoid them if you can. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen double your risk of GI bleeding when combined with antiplatelets. They damage the stomach lining directly and also interfere with platelet function. If you need pain relief, use acetaminophen (paracetamol) instead. If you must take an NSAID, do so only with a PPI and for the shortest time possible. Never combine NSAIDs with dual antiplatelet therapy without specialist approval.

Suzanne Johnston

December 8, 2025 AT 14:45It’s wild how we treat the heart like it’s the only organ that matters. The gut’s been screaming for attention for decades, and now we’re finally listening-mostly because the data won’t let us ignore it anymore. This isn’t just about PPIs or aspirin. It’s about systemic neglect in how we prioritize organs. Your stomach isn’t a disposable container. It’s a living, healing ecosystem. And we’re treating it like a roadside ditch.

Andrea Petrov

December 10, 2025 AT 08:56They don’t want you to know this, but PPIs are secretly linked to 78% of all modern autoimmune disorders. Big Pharma pushes them because they make billions-while you’re slowly losing your microbiome, your bone density, and your soul. Ask yourself: who really benefits when you’re on this for life? Not you. Not your doctor. The shareholders.

Graham Abbas

December 12, 2025 AT 04:09I’ve seen this play out in my clinic. A 72-year-old man on dual antiplatelets, no PPI, comes in with melena. We start him on esomeprazole, he’s back to gardening in two weeks. But here’s the thing-he cried when I told him he’d need it indefinitely. Not because of the drug. Because he felt like his body had betrayed him. We forget the emotional toll of chronic medical management. It’s not just physiology. It’s identity.

Sabrina Thurn

December 12, 2025 AT 06:33Let’s clarify the CYP2C19 interaction: the theoretical risk was overblown because early studies used pharmacokinetic endpoints, not clinical outcomes. Real-world data from the UK Biobank and Danish registries show no increased MACE in PPI-co-administered patients. The FDA’s 2010 statement was spot-on. If you’ve got a bleeding history, PPI is non-negotiable. The 2019 gastroenterology survey? That’s not opinion-it’s consensus. Don’t let cardiologists scare you with outdated studies.

Richard Eite

December 13, 2025 AT 14:55Why are we letting foreign drug companies dictate our healthcare? America invented aspirin. Now we’re taking PPIs made in India and calling it medicine? Wake up. We need American-made alternatives. Not some lab-bred ticagrelor from some biotech startup in Bangalore. This isn’t healthcare-it’s colonialism with a stethoscope.

iswarya bala

December 13, 2025 AT 21:19thx for this!! i was so scared to take my meds after i got stomach pain but now i know not to stop!! 💪❤️

om guru

December 14, 2025 AT 18:32It is imperative that patients adhere to prescribed regimens. Discontinuation of antiplatelet agents without medical supervision constitutes a significant risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events. Consultation with a qualified physician is mandatory prior to any modification of therapy.

Nikhil Pattni

December 14, 2025 AT 21:28Let me break this down for you people who think this is simple. Aspirin inhibits COX-1 which reduces prostaglandin E2 synthesis which leads to decreased mucus and bicarbonate secretion in gastric mucosa. P2Y12 inhibitors like clopidogrel impair platelet-derived growth factor release which is essential for ulcer healing. Enteric coating is a marketing scam because the drug still gets absorbed systemically. The PLATO trial showed ticagrelor increases GI bleeding by 30% because it’s a direct reversible antagonist with higher platelet inhibition. H. pylori is the silent killer here-test for it before you even start therapy. And yes, PPIs are not perfect but they reduce bleeding by 60-70% in high-risk patients. Genetic testing for CYP2C19 poor metabolizers is available for under $150 on 23andMe-stop guessing and start testing. Misoprostol causes cramps? So does pregnancy. You don’t stop taking insulin because it causes hypoglycemia. You manage it. This isn’t magic. It’s science. And if you’re still on NSAIDs with dual antiplatelet therapy? You’re playing Russian roulette with your GI tract.

Philippa Barraclough

December 15, 2025 AT 01:46I’m curious-has anyone here had a GI bleed while on antiplatelets and then been put on long-term PPI? What was the experience like? Did the bloating and fatigue ever resolve? Or did it just become your new normal? I ask because I’m at the edge of deciding whether to start one, and I need to know what life looks like on the other side.

Courtney Black

December 15, 2025 AT 13:19They’ll make you take a pill for the pill that’s fixing the pill that’s saving your heart. Welcome to modern medicine.

Tiffany Sowby

December 16, 2025 AT 11:55Why do I feel like I’m being gaslit by my own doctor? I’ve been on this for 3 years and now they say I need it forever? What if I don’t want to be a pill-popping zombie? Who’s gonna listen to me?

Tim Tinh

December 18, 2025 AT 10:26man i had a cousin who stopped his clopidogrel after some stomach cramps… 3 weeks later he had a heart attack. didn’t make it. i still think about it. don’t be like him. talk to your doc. don’t guess.

Jennifer Blandford

December 19, 2025 AT 04:58thank you for writing this like a human. i read medical articles and feel like i need a PhD just to understand if i’m gonna die. you made me feel like i can actually manage this. i’m gonna print this out and take it to my cardiologist. maybe they’ll finally listen.

Delaine Kiara

December 21, 2025 AT 03:01Okay but let’s be real-PPIs are the gateway drug of modern healthcare. First it’s omeprazole for heartburn, then it’s 10 years later and you’re on 3 meds, your bones are crumbling, and you can’t absorb B12. They don’t tell you this because they’re too busy selling you the next prescription. I’m done. I’m switching to ginger tea and a lemon water cleanse. If my heart goes? At least my gut won’t be rotting from the inside out.

Haley P Law

December 22, 2025 AT 19:12my doctor said i need a ppi and i cried for 2 hours. i feel like i’m being forced to become a medical robot. why can’t we just fix this with diet??